Fr 01.11.2024

DFG Research Training Group

Organizing Architectures

In the DFG Research Training Group “Organizing Architectures” (3022), in which the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, the Technical University of Darmstadt, the University of Kassel and the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory are involved, positions for doctoral students and postdocs are to be filled as of 01.11.2024.

Register here for the Q&A Meeting Organizing Architectures on July 15 at 6 pm:

https://uni-frankfurt.zoom-x.de/meeting/register/u50oceCvpzwuHtELgIt6YT7CMh1iKAahaN7b

After registration, you will receive a confirmation email with information on how to join the meeting.

Description

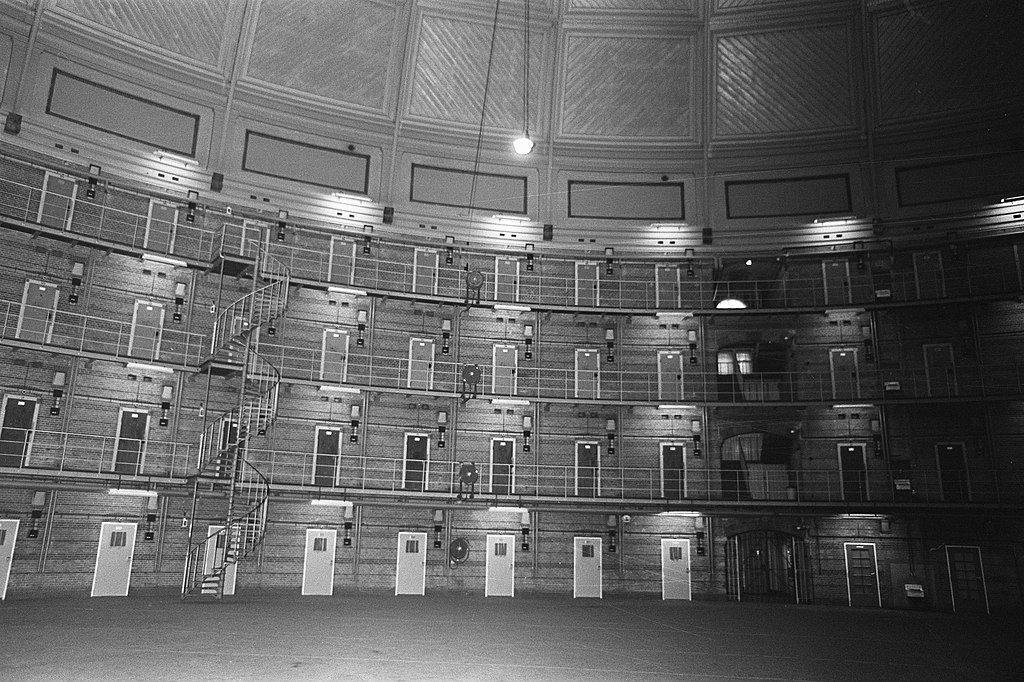

The college examines architectures as products and as impulsions for collective processes. It takes into account on the one hand the fact that complex social processes materialize, embody themselves and develop symptomatically within architectures. Built or planned structures also themselves, on the other, also organize social spaces, which in turn influence the projections of new architectures. “Organizing Architectures” aims to examine this tension between organized and organizing architectures. In doing so, the college shifts the focus from the architectural concepts and devices that have dominated European discourse to date (the creative subject, the individual artistic work, the built object as the conclusion of planning) to an examination of their processual and collective conditions. The relevance of this topic is particularly evident in view of current plans such as the linear city of Neom in Saudi Arabia, the relocation of cities with populations of millions such as such as Manila or Jakarta into planned metropolises or Elon Musk’s colony on Mars. These (in part escapist) planning fantasies reflect current crises (economic, political and climatic), but do not provide sustainable responses to them. The college therefore focuses on architectures—in view of present-day challenges and from a decidedly interdisciplinary perspective—as spaces of dynamic negotiation processes. Using modernism as a historical framework, it examines the contentious coexistence of collective and individual design power in planning processes. In addition to providing a new perspective on modern architecture, it provides important insights and contributes to raising awareness among scientists and architects regarding planning issues and their social impact.

Thematic outline

By considering architecture as something organized and organizing, the college draws attention to the collectivities and processualities of planning as well as to their social dynamics. The prerequisite for this is a strongly interdisciplinary orientation with the potential to structurally and permanently link previously separate discourses that are of central importance to the topic: architectural and social history, sociology, urban planning, media studies, legal history and human geography perspectives all complement each other in the research of architecture as multi-perspective phenomena and instruments. Historically speaking, the examination of modern architecture represents an ideal starting point for this project. Large-scale projects such as “New Frankfurt” in particular were shaped by the belief that society could be organized using organizational planning concepts. These and other programs were initiated by bourgeois-liberal forces who saw the “people’s state” as a “technical work of art”. The implementation of organizational structures that made large-scale planning possible was inseparably linked to the aestheticization of the modern nation state (in both Europe and in its former colonies). Accordingly, what is built is not only to be understood as the materialization of rationalization processes. In a kind of feedback effect, it produces aesthetic effects that essentially determine perception and self-image, and thus also the character of organizations and institutions.

The convergence of architectural, state and general organizational functionality (especially since the 18th century) is evident in the transfer of the concept of function from official and scientific language to architecture, or in the development of new procedural and presentation formats such as state-regulated competitions and building exhibitions. Accordingly, they not only conveyed avant-garde architectural models, but also new “spatial orders”. Examples of this include the exhibition “The Apartment” in Stuttgart (1927) and the “Section Allemande” at the exhibition of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris (1930). Even before this, institutions such as the Royal Institute of British Architects (1872) and the Association of German Architects and Engineers Associations (1897) had striven to standardize architectural competitions and triggered a series of ever-newer competition regulations that continue to this day. They represented an important selection tool, with the help of which the state, politics and economy could exert a direct influence on contemporary architectural production. As the example of the influential juror Max Bächer in the second half of the 20th century shows, this was associated to a considerable extent with opportunities for discourse control, patronage and design and planning intervention. However, this does not only apply to state institutions and was by no means limited to the area of planning. Networks of architects, historians, planners, politicians and theorists, from the CIAM (Mumford 2000) to the Anyone Corporation, competed in new ways for discursive-spatial interpretive sovereignty on questions of architecture, urban planning and architectural theory.

The college understands the functionalities of architecture as inseparably linked to the functionalities of the body politic, as expressed in its organizational regimes, its practices and media of discourse management, canonization, norming and standardization, but also in relation to organized counter-movements. The former has been true not only since the paradigmatic Haussmannisation of Paris (1853-1870) or for the Zoning Law of Manhattan (1915), and generally for urban visions of modernity such as Ludwig Hilberseimer’s “Großstadt” (1927) or Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse (1930). This connection is particularly clear in the European colonies. It is precisely in the development from imperialism to the modern state that it becomes clear how the logistical and rationalized construction of the state through organizations, laws, networks etc. not only served colonization, but also political-economic exploitation in the colonies themselves. This has already been demonstrated in the examples of India, southwestern Africa and Algeria. In recent years, the effects of postcolonialism, late capitalism, neoliberalism and globalization on the production of architecture and space have also become the focus of critical-historical studies.

The organized (and organizing) architectures of modernity are by no means limited to the narrower framework of a structural-spatial design of the environment by architects, certain aesthetic programs or architectural theoretical legitimations. They arise primarily through consortia, cooperatives, cooperations, planning collectives, decision-making bodies and legislation that strive to shape society or even control it on the basis of ideological-political, hygienic, economic and ecological objectives. They derive authority from the design or construction experience of their actors and from the internal logic of sometimes complex procedures. Their administrative-bureaucratic structures, control elements, selection procedures and visualization strategies are intended to ensure objectivity where societies threaten to fall apart into subjective life plans and disorder. Here, more than anywhere else, social ideas of order are linked to a normative claim to reality that is often in contradiction to the reality of life. In addition to the organizational and order regimes manifested therein, processes of non-state appropriation, redefinition or occupation of architectural and urban spaces are also of great interest, as is the organization of those who wanted to participate in spatial design but could not or were not allowed to. Examples of this would be practices of squatting, the Occupy Movement, the establishment of informal do-it-yourself archives, the protests in the Hambach Forest or #BlackLivesMatter, as well as protest architectures, including the deinstallation and relocation of monuments as spatial-political forms of organization. Methodologically, the change of perspective away from official narratives is of particular interest, for example through oral histories of various interest groups and protagonists in order to close archival gaps as well as a reorganization of architectural knowledge and spatial perception through feminist and queer spatial theories. Since architecture as a practice is still dominated by the myth of a white male designer, a historical-critical reappraisal of its complex history is also required here in order to document and promote accessibility and equal participation of groups as diverse as possible. Therefore, the focus of the college is not only on questions of structures in architecture (and thus also of control and power), but also on the expansion and on the breaking of canonical conventions by including diverse perspectives, as thematic and content diversity cannot be simulated in science but must be concretely implemented and lived.

Approach, methods, innovative content

The Research Training Group focuses on the tension between projective and reactive processes in architectural production. Following recent research, it no longer sees architecture as a built solitarily. In addition to urban ensembles, we understand architecture as infrastructure. The college also sees architecture as a discourse between actors from different professions and ambitions, since the consideration of social orders cannot be separated from architectural orders. What is to be understood as architecture in each specific case is based on complex social negotiation processes. Accordingly, we do not understand the adjective “modern” as a primary attribute according to a stylistic or aesthetic classification of architecture, but rather as its contextual framework. At the same time, the college pursues a systematic approach based on interdisciplinary approaches (architecture and art history, architectural theory, legal history, history, political and media studies, human geography, urban planning and sociology) that allows both historical analyses and diachronic comparisons and contemporary analyses. In doing so, it combines methods usually used separately from institutional, organizational, planning and state theory, political iconography, architectural sociology, discourse analysis, media and network theory. This makes it possible to subject basic assumptions of architectural history and theory to a critical revision in an innovative way. On this basis, new research questions are to be developed along the partially overlapping order regimes of organized modernity (liberalism, nationalism, fascism, socialism, capitalism etc.). Transparency, function, rationality and order are accordingly understood as concepts embedded in the overall societal organization of spatial, social and territorial regulatory power.

Fields of work

In the three fields of work “Institutions”, “Networks” and “Discourses”, the college examines the genesis of organized and organizing architectures, their consequences for social spaces and planning development options. We do not consider the three fields of work mentioned above scientific perspectives that can be precisely separated from one another. The question of institutions, networks and discourses forms the common framework for all those involved, regardless of the historically and methodologically different approaches of the college. An analysis of institutions focuses on the mutual dependencies of actors in systems; an examination of networks enables insights into far-reaching interrelationships and their structural conditions; in the study of discourses the construction of narratives and canons is examined, as well as questions of reception and modeling. The college thus challenges young academics to research architectures in an interdisciplinary manner as products of complex, collective and organized practices within overall social and political processes so as to take into account their polycausal emergences and impacts. Accordingly, scientists from different disciplines and research areas are involved, offering the fellows different perspectives on architecture.

Field of work 1: Institutions

The focus of the field of institutions is on processes of controlled orientation, regulation and “organization” of processes, people and things. Here, concepts of efficiency, functionality, historicity, hygiene, objectivity, rationality, precision, sustainability, normativity, professionalization, participation, security and transparency as well as their media representations come to the fore and are examined for their legitimizing, discourse-controlling and aesthetic functions. Historically, the bureaucratic-administrative shifts in planning activities occurred through the implementation of senior building directorates and construction and planning departments, the differentiation of a formalized contract and competition procedure, the institutionalized training in construction academies and technical universities, the legal regulation of planning, construction and competition processes, the founding of architects’ associations and interest groups and organizations such as the Association of German Architects in 1903 in Frankfurt am Main and the German Werkbund in 1907 in Munich. With the totalitarian regimes of the early 20th century, a further wave of state influence on planning practice and its bureaucratization can be observed. The associated ideals and ideologies continued to have an impact on planning discourses well beyond the 1960s. After the War, numerous large-scale projects emerged at the municipal level, such as the banlieues in France, which particularly combined political programs, social science research, current social issues, collective identity formation processes, findings from the international planning discourse and reforms in architectural training. In recent years, the architecture of state, non-governmental, and supranational organizations such as UNESCO, the UN and the EU but also of property developers, companies, banks and insurance companies and regulatory bodies have become the focus of research. The field of work continues to research these developments, which are eminently important for the history of architecture, and incorporates fundamental findings from organizational sociology, institutional analysis and administrative sciences. In doing so, the college fundamentally assumes that the “embodied self-representation of an order” through the “symbolic coding power of architecture” (Rehberg 2009) is a decisive criterion for the legitimacy of institutions. Research questions arise, for example, from the following objects of investigation: collective and official planning and monument preservation, archives, political decision-making processes, standardization, legislation, institutional legitimation strategies, media representation requirements, competition procedures, participation strategies and the entire unregulated area of informal practices, including deviations and permitted violations of rules as well as the media-technological organization of design, but also the architectural-monumental embodiment of institutions as well as patriarchal structures, processes and role models.

Field of work 2: Networks

Parallel to the institutionalization processes of modernity, a polycentric understanding of space is becoming increasingly important: road and rail systems, for example, have been presented as networks since the end of the 18th century, and garden cities and settlement complexes as nodes connected to one another via transport and communication routes. In the age of digitalization, increasingly complex spatial configurations that develop their own specific topography beyond real places are emerging. The college is not only interested in the concept of networks as a historical or contemporary phenomenon of an infrastructural and media-technological reorganization of space. Building on cultural studies interpretations, it sees it as a cultural technique that is more effective today than ever before and that organizes relationships between living beings, things and ideas in a comprehensive sense. Accordingly, the field of work deals not only with the materially constructed network, but also with the network in its social and societal conception as a complex of actors, media and objects, but also of institutions and organizations. In view of this hybrid nature of networks, following numerous reflections on the concept of network at the beginning of this century, the question arises of whether the “dichotomy between culture and nature” (Rudolph-Cleff/Gehrmann 2020), between “organic” and “artificial” (Böhme 2004), between real presence and media, reality should not be viewed as a modern myth (Latour 2007; Latour/Yaneva 2008; Martin 2003). This should be examined in particular with regard to the assumption of an ontological difference between the creative subject and the organizations, institutions, networks and media that are, as it were, object-like in opposition to it. In view of a world that is increasingly structured in a network-like manner, the question of the cognitive potential of such explanatory models for the investigation of formalized planning processes, normative visualization strategies, organizational-institutional procedures and expert cultures is more important than ever. Within the framework of the college, the concept of the network takes on the overriding importance of an instrument of knowledge. Unlike previous research on the biographical interrelationships of the protagonists in the history of architecture, the focus of the field of work is on organizational processes, political alliances, economic dependencies and institutionalizations as well as their representative and bureaucratic forms. Structures of associations, clubs, chambers, representatives of the construction industry as well as private and informal networks and their forms of “organization”, such as organizational charts, distribution of responsibilities, forms of exchange, type of meetings and communication media, are examined. Aspects such as interest representation, self-administration, collectivization and exchange, distinction and group dynamics play a role: interpersonal representations (who represents whose interests in which networks, which configurations reflect the interests of which groups), but also instructions for action and target agreements from NGOs or the UN, as well as local measures such as citizens’ initiatives or participation in planning processes, are brought together with questions of diversity and (different) visibility of the groups and actors, protest and alternative movements involved.

Field of work 3: Discourses

The college investigates how discourse spaces are constructed and deconstructed, which medialities and archives are used or ignored as evidence and justification, and how scientific discourse formation manifests itself in architectural forms. As a condition of architecture-relevant discourses, disciplinary, social, spatial and digital accessibility and inaccessibility must be taken into account, as must the question of how discourse dominance is structurally created, defended and contested. In modern times, public interest in architecture is linked to new formats and media of reflection such as essays, reports, polemics, critiques and manifestos. Modernist architecture also increasingly served to project ideological-political ideas of order and institutional self-presentation. Both can easily be understood from the prominence of new building projects (museums, parliamentary buildings, banks, stock exchanges etc.) and the social debates that continue to be sparked by them today. Examples include the Palais de Justice de Bruxelles (1866-1883), the projects of Georges-Eugène Baron Haussmann in Paris (1853-1870), the Palais des Nations in Geneva (1927) and the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. More recently, for example, the capital city plans in Berlin, Ground Zero in New York or the new old town in Frankfurt have led to this. With the emergence of corporate organizations such as corporations themselves and interest groups, such as associations or alliances, at the end of the 19th century on the one hand, and the expansion of the state’s sphere of intervention on the other, an ever-closer intertwining of politics, business and the state can be observed (Habermas 1990). Since the growing influence of mass media in the early 20th century and finally with globalization and digitization in the 21st century, such interrelations have reached their temporary peak. In more recent developments, real-world laboratories are playing an increasingly important role in urban development, in which, in addition to temporary changes in public space (e.g. closure to motorized traffic), data on the associated goals (e.g. more cyclists) are collected. The extent to which the findings obtained in this way flow into the political and social discourse and influence longer-term planning has so far been little investigated. Central to the field of work is the question of the (more or less structural) involvement of various actors and interest groups. Concepts such as the “mouthpiece”, representation and agency, ideologies and ways of life, connection with political interests and forms and possibilities of criticism are becoming relevant. Of interest are narratives, media reports (e.g. Who writes where, when and how about construction projects?), digital platforms and mediation offers such as exhibitions and guided tours as well as all forms of architectural criticism and journalism.

| Principal Investigators | Field of Research |

| Prof. Dr. Jens Borchert | Politische Soziologie/Staatstheorie (GU) |

| PD Dr. Peter Collin | Europäische Rechtsgeschichte (MPI) |

| Prof. Dr. Andreas Fahrmeir | Neuere Geschichte (GU) |

| Prof.’in Dr. Sybille Frank | Stadt- und Raumsoziologie (TUDa) |

| Prof.’in Dr. Susanne Heeg, Susanne | Geographische Stadtforschung (GU) |

| Prof. Dr. Rembert Hüser | Medienwissenschaft (GU) |

| Prof. Dr. Martin Knöll | Entwerfen und Stadtplanung (TUDa) |

| Prof.’in Dr. Antje Krause-Wahl | Gegenwartskunstgeschichte (GU) |

| Prof. Dr. Carsten Ruhl | Architekturgeschichte (GU) |

| Prof.’in Dr. Christiane Salge | Architektur- und Kunstgeschichte (TUDa) |

| Prof.’in Dr. Annette Rudolph-Cleff | Entwerfen und Stadtentwicklung (TUDa) |

| Prof.’in PhD Alla Vronskaya | Geschichte und Theorie der Architektur (UK) |